Reflections under a tree

A couple of weeks ago, I interviewed a lovely woman for my second book ‘Little Tufts of Tea’. We sat outside a coffee shop (drinking tea - obviously), then as the sun became too warm, we moved to a bench under a shady tree.

This woman told me how, as a young girl, she had been brought to her Nan’s house by her parents aged 7, and left there. Her parents did come back for her, then split up, there were various moves and different living arrangements, and by the age of 15 she was back with her Nan, just the two of them. She does not look back on her childhood as one of disruption and pain, but one of wonder and love, because of her Nan.

As we sat under the tree, we spoke for an hour and a half without pause. It felt like five minutes. I learned so much about both her and her nan - who has long since passed - and was blanketed in the comforting memories of their relationship and the connection and love that was shared through tea and toast. It was so beautiful.

I felt like I was in the kitchen of her childhood with this powerhouse of a woman: a passionate supporter of youth, who worked in ‘borstals’, had a cheeky interaction with Lord Linley, and always, but always had lashings of tea and toast on hand for the teenage friends that would barrel out of school and into their home, innately sensing that this was a place of safety without even realising it. I could almost see her hand reaching for the kettle.

We spoke about all sorts of facets of their life together, and the overriding feeling was one of absolute care. It was such a gorgeous conversation, and as we finished up (for now), I told her how grateful I was for her time, for her openness and sharing her story, and for letting me immerse in the memories she held of her Nan. It was so very precious.

Her response was, ‘no, thank you. It’s been a joy to talk about her. It’s not something I ever get to do’. We were both deeply touched by the exchange.

Will you be my friend?

Her closing comment made me really reflect on what a rare treasure it is to speak of our lost loved ones in this way.

In the aftermath of loss, there are definite stages of where and when we talk about them. I remember the day that my brother, Brian, died, I went through his entire phone book (and mine) and rang everyone and told them. It was possibly really odd behaviour and I kind of cringe when I think back on it now. I just knew I only had a finite capacity for uttering the words, so I rang people who I didn’t really know to say, ‘hello, I’m Brian’s sister, he died this morning’. In that phase, it was all about letting people know, being in ‘broadcast’ mode, and fielding inappropriate questions from well-meaning (often sobbing) people about how? Why? How could it be?

A couple of months later, with my job having relocated during the time I was on my first maternity leave (the period when he died), I found myself living in a new area with no friends, freshly bereaved, with a poorly newborn baby. That was a treat. Being surrounded by people I didn’t know, I somehow needed to convey what was happening with me. I couldn’t make sense of it myself so perhaps explaining it to others would help?

I would take my mini-baby-Bel down to the playground and push her in a swing hoping to connect with other new mums in that way that you do when you’re all desperate, sleep deprived and screaming inside...

At this point Brian still consumed my every waking thought, and I would find myself introducing myself with ‘Hi, I’m Emma. My brother just died. Would you like my phone number?’

I didn’t get much uptake.

The Period of the Great Silence

Once the visceral need to talk about ‘the event’ died down (pun intended), there was a long period where he wasn’t talked about at all. Everybody knew what had happened, so we didn’t need to verbalise it any more. The family gatherings had an obvious gaping hole, but we just wafted past it like it wasn’t there. In case there lay a possibility that someone was having brief respite from their grief, no one dared to bring it into the ‘now’. I shall call that the Period of the Great Silence. (Although as a parent myself, I now realise that there would never have been a moment my mum and dad did not have him in their ‘now’).

Subtly and slowly over a number of years, however, we snuck him back in. ‘Brian used to love that’. ‘Oh that reminds me of Brian’. ‘Remember when Brian did this?’. I could tentatively speak his name without feeling like I was stabbing my parents or my sister in the heart.

We could even raise a glass.

The joy of remembering

Fast forward 15 years, and I can speak of him in a very different way, without the agony, and with much joy, yet now I don’t often get the opportunity. Those that have known me forever know all about him, and what happened. Those that have met me in the interim have learned the bones of what happened as we have shared our histories over cups of tea glasses of wine. Sometimes my children ask me aspects about the Uncle they will never know. It wasn’t until very recently, however, that I got to actually talk about him, as opposed to what happened to our family.

A new friend, and one I just know he would have fancied (and tried to rescue - he was a rescuer), said to me one evening ‘tell me about Brian’. She wanted to know what he was like, as a person.

Wow.

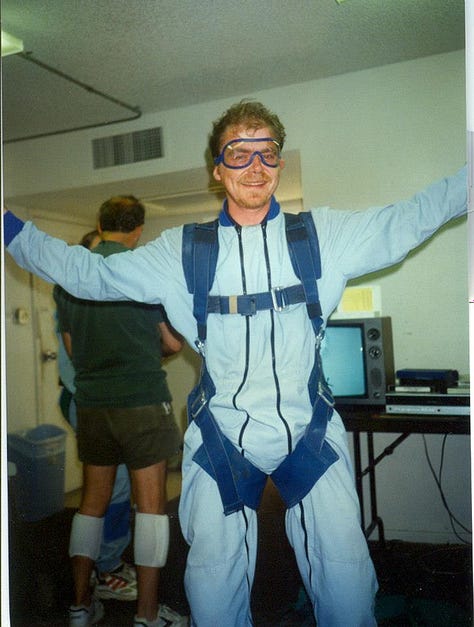

As I described him and told stories of him, I felt the same joy that my lovely new tea friend did when telling me about her Nan. I spoke of his mischievousness, of him and his best mate throwing their school books in the river, balancing the seesaw between ‘cheeky’ and ‘naughty’. I recalled how we climbed trees together and read the Beano, about ‘quarters’ of cola bottles and sherbert pips. How he later rolled me my first spliff - my definition of ‘quarter’ having evolved by then - and dated my friends (and me, his); how we listened to each other’s young adult heartache and lit flaming sambucca’s in each others mouths. How he travelled the world despite his health limitations, doing parachute jumps and flying, with always the time to stop and hug a horse.

A pain in the arse

I loved recalling his fierce sense of loyalty and justice, his fucking hilarious sense of humour and inimitable cackle. But like the stories I listened to of ‘Nan’ - my new friend and I are both minded not to deify our loved ones, noting their capability to be ‘an utter pain in the arse’.

And yes, of course he was an utter pain in the arse. He could be a total shit. He was my big brother. I could have throttled him a thousand times, and probably tried once or twice, but that’s not a patch on the good times. I’m just so grateful that someone asked me to tell them about him in this way, and allowed me to soak in the memory of it all.

There is so much more to share, and I’ve discovered a new joy in remembering him in this way. It’s time for me to allow myself this part of the story, and that’s ok.

How do you feel about talking about your loved ones?

Do you find you are stuck in the story of their loss or of what happened and the impact?

How would you feel about remembering them in this way?

I’d love to hear.

Love & Lemons 💕🍋

Em x

It is a joy to remember him, the wisdom, the empathy, the giggling, the wisecracks. I love the fact he’s still in my dreams, not doing anything special, just being there, as if he still is. Lovely words as always 💕💕

Beautiful 💖🩵